watch ’em #02

by markusfb

this post is part of the #criterionblogathon thx for bearing with my broken english. please beware: spoilers might be lurking.

here we go…

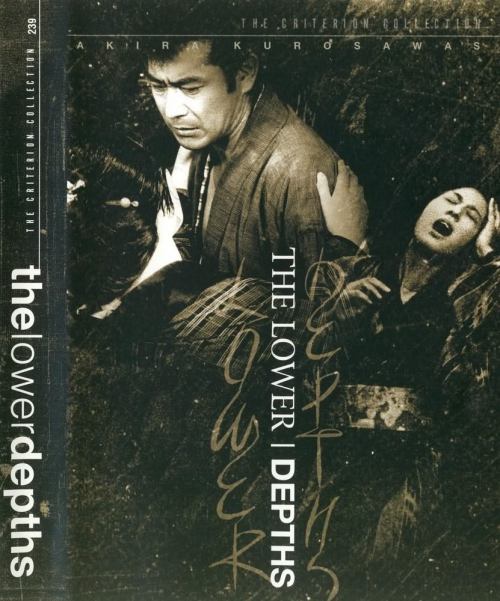

“the lower depths”

THE CRITERION COLLECTION #239

DVD BOX SET – 2 Discs

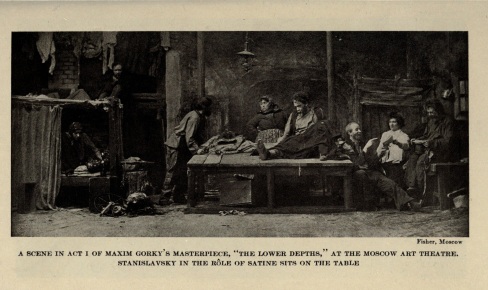

THE LOWER DEPTHS [or A Night’s Lodging] portrays a lodging house, hideous and foul, where gather the social derelicts — the thief, the gambler, the ex-artist, the ex-aristocrat, the prostitute. All of them had at one time an ambition, a goal, but because of their lack of will and the injustice and cruelty of the world, they were forced into the depths and cast back whenever they attempted to rise. They are the superfluous ones, dehumanized and brutalized.

originally published in The Social Significance of the Modern Drama. Emma Goldman. Boston: Richard G. Badger, 1914. pp. 295-301.

the template:

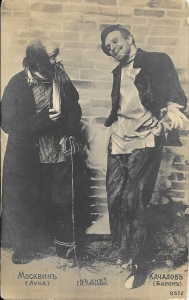

The play The Lower Depths (На дне, subtitled: „Scenes from Russian Life”) was written by Russian and Soviet writer Maxim Gorky (*28.3.1868 – †18.6.1936) in 1902. Born as Alexei Maximovich Peshkov, he adopted the pseudonym “Gorky” (from горький; literally „bitter”), which reflects the topics he tackled and a growing sentiment towards society and social life in general in the Russian Empire of the early 20th century.

The people he depicted, were generally poor and from the lowest strata of society. He was looking for character and pride amongst them – for the underlying humanity beneath all fight against grinding poverty, cruelty and harsh climate, which formed their bitter fate. Gorky portrayed loosers, outcasts and misfits, trying to find out, what hold them back at succeeding in life. He believed in the uniqueness, dignity and value of every single human – notwithstanding gender, education or wealth. The underlying motive in most of Gorkys writing has to be hope in the power of faith to overcome hardship. But always countered with his skepticism towards the injustice of inevitable fate.

The reception by his audience was hostile. Though considered a masterpiece today and soon after its premiere becoming a worldwide theatrical success, the initial reaction in Russia was quite different: Portraying the lowest of society was a scandalous topic for most his middle class viewers, who were deeply rooted in the feudal system of czarist Russia 15 years prior to the Russian Revolution.

When debuting, the play was dismissed as missing a plot and being much too pessimistic and sarcastic, the ambiguity of his ethical messages bewildered many viewers. Dark, dirty and of unfamiliar realism, „The Lower Depth“ seem odd, unsettling and uncomfortable to watch and established a new form of Russian social realism. His sympathy for the Russian city proletariat and his general human beliefs nevertheless lead Gorky to promote the emerging Marxistsocial-democratic movement, which adopted him as an intellectual poster child for decades to come.

disc 1

„Les Bas-fonds” (french for: The lower depths), 1936

Directed by Jean Renoir (*15.9. 1894 – †12.2.1979)

Produced by Alexandre Kamenka

Jean Gabin as Wasska Pépel (the thief)

Louis Jouvet as the baron

Suzy Prim as Vassilissa Kostyleva (the landlady)

Junie Astor as Natascha (her sister)

Vladimir Sokoloff as Kostylev (her husband)

Jany Holt as Nastia (the prostitute)

Robert Le Vigan as the alcoholic actor

Paul Temps as Satine

Robert Ozanne as Jabot de Travers

Henri Saint-Isle as Kletsch (Anna’s husband)

Nathalie Alexeff as Anna

André Gabriello as Felix (the servant)

Maurice Baquet as Aloucha (the musician)

Camille Bert as the count

René Génin as Luka (the pilgrim)

The Film

Renoirs film strays away from the original play be Gorky, for he centers the story around two marvelous actors: Renoir cast emerging French superstar Jean Gabin as thief Pepél and irrepressibly magnetic stage actor Louis Jouvet for the role of the gambling baron. The director would team up with Gabin for a couple of times in the following years, choosing him for the leading role of the anti war movie „La Grande Illusion“ (1937, CRITERION COLLECTION #1) and directing Gabins pet project „La Bête humaine“ (1938, CRITERION COLLECTION #238), a thriller depicting the work and life of train engineers, which Gabin fancied at that time.

Gorkys original play takes place solely in a rotten flophouse and circles around the outcasts who find their home in the lowest of dumps. But Renoir decided to move more than half of his movie outside the depressing shelter and into the light side of life, depicting wealthy citizens and aristocracy, gambling for high stakes, drinking, eating out, laughing… a sharp contrast to everybody’s life in the shelter and especially the exact opposite of the thief’s world.

Gabin’s Pepél lives and works in hiding. He knows darkness, shadows and fear all too well. Eventually he sets out to rob a downtown luxury home, which is owned by the baron (L. Jouvet). He finds no money at all, but ultimately gets caught by the amused, relaxed aristocrat, who convinces him, that he lost all his money gambling, and that there is really nothing left to steal in his apartment. The two totally different characters make friends and share a night of feasting, drinking and gambling.

They dream and muse about the simple joys of life, like to just lie in the grass on a river bend and watch the clouds. For different reasons, both wish their lives may change to the lighter, simpler side. They get really close but seem to form ideas about their future that separate them again. But in a different way, than by what distinguishes their social status up to this point. It all seems like a last meal of sorts, and when the two split in the early morning, the viewer is under the impression, that the life of both took a funny turn in an totally new direction.

Without giving too much of the plot away, Renoirs film is focused on the idea, that most people are trapped within their role and struggle to free themselves from the bonds, that tie them. But these obstacles can be overcome. Pépel once utters, that he „is a thief, a pickpocket and always was.” That – when he was young – he was called „son of a thief“ and nobody came along to call him anything else. But Pépel wants to change and strives for love and a new beginning. And there is hope that he might be able to flee the hideous flophouse for greener pastures.

The baron on the other side was born rich and privileged, but starts to realize, that wealth and money in general are not what he cares for at all, but the pure joy and passion of play. And maybe he might find as much joy in gambling for a few cents in a lowly shack, than betting thousands in an upper-class casino. This hope, this faith in the chance to change, is the fundamental difference between Renoir’s optimistic film and Gorky’s depressing play. In the light of the emerging fascist movement all around Europe and the Popular Front in America as well as France in 1936, Renoir turned Gorky’s fatalism into a world of open, presumably happy endings.

To find a new direction and meaning in life is key to Renoir. Overturning the odds is symbolized by people moving in and out of the flophouse. Not everything has a good ending, not everybody makes it, but there is hope to find luck and happiness for some. Just imagine: one would move in – without regret – freed from the burden of property. Another moves out for good – freed from crippling fatalism. Both freed from the bounds of heritage. What has grown unbearable for one, could be liberating for the other. Rid from fruitless illusions one sees the future bright and clear.

Heaven and hell – which is which? It solely seems to lie in the eye of the beholder.

the verdict

A true lighthearted take on the grim subject, which could have been a masterpiece, if not for the awful performance of Jean Astor, who deliverers nothing but bleakness (Renoir was forced to cast her by producer Andre Kamenka) in her role as Natasha, and nearly ruins the marvelous play of the duo Gabin and Jouvet. Still there’s so much to be seen here…

…too good, to be missed. watch it.

disc 2

„どん底 Donzoko” (Japanese for: The lower depths), 1957

Directed by Akira Kurosawa (*23.3.1910 – †6.9.1998)

Produced by Akira Kurosawa, Shojiro Motoki

Toshiro Mifune as Sutekichi (the thief)

Isuzu Yamada as Osugi (the landlady)

Kyōko Kagawa as Okayo (her sister)

Ganjirō Nakamura as Rokubei (her husband)

Koji Mitsui as Yoshisaburo (the gambler)

Kamatari Fujiwara as the actor

Akemi Negishi as Osen (the prostitute)

Minoru Chiaki as Tonosama (the ex-samurai)

Nijiko Kiyokawa as Otaki (the candy vendor)

Eijirō Tōno as Tomekichi (the tinker)

Eiko Miyoshi as Asa (Tomekichi’s wife)

Kichijiro Ueda as Shimazo (the police agent)

Haruo Tanaka as Tatsu (the cooper)

Bokuzen Hidari as Kahei (the pilgrim)

Yū Fujiki as Unokichi (the cobbler)

The Film

Kurosawa loved international stage drama, for he did not only brought Gorky’s work to the big screen, but also directed new versions of plays by Dostojewskiy („the Idiot“, 1951 CRITERION COLLECTION ECLIPSE SERIES 7) and Shakespeare „Ran“, 1985 THE CRITERION COLLECTION #316 and „Throne of blood“, 1957 CRITERION COLLECTION #190 )which are based on King Lear and Macbeth respectively). He had the firm belief, that the social questions and moral dilemmas emphasized by these foreign dramatists needed to be transformed for the new medium film and put into a more familiar context to school a broader audience in Japan. Fate, prejudice, humanity and ultimately: violence form a context that built the cornerstones of his work and constantly affected his decisions for new projects. As is the recurring theme of people giving in to their illusions towards life in general.

So the legendary Japanese director tackles the topic from a totally different angle than his French peer Jean Renoir. He stays very close to the original play though moving the setting to the Japanese Edo-period which he decided with scriptwriter Hideo Oguni to make the topic more accessible for Japanese viewers. The poverty in Imperial Russia at the beginning of the 20th century stands in stark contrast to the aristocrat life of the reigning classes. This is resembled very well by the relation between Japanese commons and the riches of their sovereigns in the middle of the 19th century. Though you also could suspect a little irony. Was this really the same Edo-period, many Japanese thought to be a most heroic one, with proud samurai fighting for truth and honor?

Kurosawa and his crew (mainly art director Yoshiro Muraki) put excessive research into building the set as faithfully to the era as possible. The architectural design of the skew flophouse makes for a building which appears to collapse every second and looks to be hold together only by sheer magic and the dirt in all its crooks and nooks. It serves not only as main stage for the superb ensemble cast, but seems to constantly bend, stretch and groan under the heavy weight of its low, patched roof. The house might be living a life of its own, resembling its lost and battered inhabitants in a strange and haunting way:

Who will give up first against the powers of life and nature?

The run down place: pegged, with rotten timber, torn paper windows and buckled frame…?

…or its dwellers: equally slouching, bruised and banged up, squeezing in the shadows of what has to be their final refuge?

The dreary folk, that has been thrown together in this urban slump, roughly one century ago, is portrayed by a true all star class of Japanese performing: Spearheaded by Kurosawa’s favorite Toshiro Mifune as Sutekichi, the thief, the cast highlights many well known and beloved Japanese stage and film actors who earned numerous accolades like Kyōko Kagawa („Tokyo Story “, 1953 CRITERION COLLECTION #217), „Sansho the Bailiff“, 1954 CRITERION COLLECTION #386), Kurosawa’s mainstay Kamatari Fujiwara who participated in eleven films of the master director or Eijiriō Tōno who, in a career lasting more than 50 years, appeared in a staggering 400 television shows, nearly 250 films.

These bona fide actors carry the play in said flophouse at the bottom of the large hole, which by the way is confused by people living outside the hole for a garbage dump. Kurosawa does rarely move the plot out of the shack for 1:30 hours and concentrates on the poor souls and their illusions. Especially how these illusions conflict with reality. It is easier to invent somebody who you want to be, than face the truth. Dreams that will stay unfulfilled and memories that never happened – harsh truth versus the comforting illusion are omnipresent in this adaptation. Still. the radical change in approach Kurosawa chooses, is that he tries to see the story as a comedy and not a tragedy, as it was originally intended. This is a very Japanese way of seeing things as opposed to the melancholy Russian soul. Everybody turns against everybody else’s stories and illusions cause it makes themselves stronger in their own idea of truth, but always in a humorous way. Though cruel and unforgiven at most times, the residents always feel the bond that binds them and laugh in the face of adversity.

The camera doesn’t move a lot which produces a strange feeling of high theatricality. Sometimes the viewer tends to forget he watches a movie but seems to be sucked in a stage play. However the presentation is very cinematic all the time. The shots are very long, which enhances the felling of watching a staged play.

This is an ensemble play. No real hero to identify with. Kurosawa doesn’t want us to feel empathy towards the characters. The viewer is a mere bystander, examining the characters more, than feeling any closeness. Their performances are leveled in a way, so that nobody really stands out. People who who don’t withstand the rotten conditions of life around them are countered by ones, that are proud of their natural gifts, their dignity and strength… people who won’t succumb. Kurosawa is clearly not interested in driving a formal plot, but in creating memorable characters.

The gambler for instance stands out as the only cynical character. Shattered, lost, hopeless, completely disillusioned and rid of all his former beliefs. His pessimism counters the underlying positive message, that all this dreaming of a better future might be human and important for mankind in general.

The priest is the quite opposite to the gambler, he preaches belief and tries to mediate all the conflicting tempers and egos within the group of residents. He tries to understand and console the broken souls with his faith in a noble cause and generously comforts the doomed.

Toshiro Mifune plays his usual self as the thief: The strong, delusional, handsome rogue with a egocentric, no-holds-barred attitude and a softer heart than he likes to commit. He has an ill-fated love interest… or two really, or even three maybe?

Was the thief a samurai once? Did the prostitute once have a lover? Reality versus wishful thinking. Lies versus truth, past versus presence.

Illusions, illusion, illusions. Everybody thinks he is somebody else. Everybody hides in a shell. But the shells will be broken. Trust me.

the verdict

the verdict

A bit to slow for my personal taste, a bit to long and a tiny bit to boring to watch in Japanese with english subtitles. Nevertheless, “The Lower Depths” is still great theatre… oops… cinema. The acting is superb, and the underlying message and morale of this play can force the willing viewer to think about his own demeanor towards the poor, might make him identify his own demons and might crack his own shell just a little bit…

…too good, to be missed. watch it.

the features

SPECIAL EDITION DOUBLE–DISC SET:

- New high-definition digital transfers of both films, with restored image and sound

- Audio commentary on Kurosawa’s The Lower Depths featuring Japanese-film expert Donald Richie (A Hundred Years of Japanese Film)

- A 33-minute documentary on Kurosawa’s The Lower Depths from the series Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create, including interviews with Kurosawa, actress Kyoko Kagawa, art director Yoshiro Muraki, and others

- Introduction to Jean Renoir’s The Lower Depths by the director

- Cast biographies for Kurosawa’s The Lower Depths by Stephen Prince, author of The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa

- Original theatrical trailer for Kurosawa’s The Lower Depths

- New essay by Keiko McDonald (From Book to Screen: Modern Japanese Literature in Films_) and Thomas Rimer (_A Reader’s Guide to Japanese Literature) for the Kurosawa film; new essay by film scholar Alexander Sesonske, author of Jean Renoir: The French Films 1924-1939, for the Renoir

- New and improved subtitle translations

- Optimal image quality: RSDL dual-layer editionsNew cover by Lucien S. Y. Yang

Wow – sounds like Criterion really outdid themselves with this set. Both films sound fascinating…and that’s due to your review. By providing such detailed background information, you’ve placed these films neatly in context for us. I think Criterion should include your research as part of the box set! 🙂

Thanks so much for joining the blogathon!

thank you very much. I’m happy you like the piece 🙂

Nice look at the different adaptations and I liked the background you included, for people who haven’t seen one or both, this makes a fine intro as well as a nice analysis. Thanks for taking part in the blogathon!

my pleasure. thx for your kind words 🙂

[…] //lillybelle.productions – The Lower Depths (x2). Great background info on both Renoir and Kurosawa’s adaptations. One of the few Kurosawa/Mifune collaborations I have yet to see. […]

Great post, Markus. I’ve seen both and happen to use Monsieur Gabin as my avatar, so you know I am a fan. I was thrilled to see you were tackling this boxset and you did it justice. I like that you compared both to the Gorky play, which I have not read. I also prefer the Renoir version and found the Kurosawa to be a slog (and I’m usually someone who doesn’t complain about slow movies.). The Renoir really does speak to the times after the collapse of the Popular Front and the pessimism that followed. This is a fantastic example of the Dark Realism that would become common in the late 1930s.

Thanks so much for participating! Really enjoyed your post!

thx aaron. yeah, I’m a fan of both: kurosawa and renoir. but if I had to pick one, I’d take the eternal coolness of Gabin over Mifune’s rage… this time 🙂

[…] // Lillybelle Production – The Lower Depths (1936 vs. 1957) […]

Great, comprehensive post.

thx!

I’ve not gotten around to seeing the Renoir version, and I haven’t watched the Kurosawa version in a long time (I remember liking it a lot, though not putting in in his top tier), but your review makes me want to revisit the Kurosawa and watch the Renoir. Nice write-up.

thx alot!